I’ve described the most likely path of the Lombard migration here. There’s just one outstanding question–where exactly is the “King’s Mountain” described by Paul the Deacon?

The hunt for this peak has informed–and distorted–the historical account of the Lombards’ travels for years.

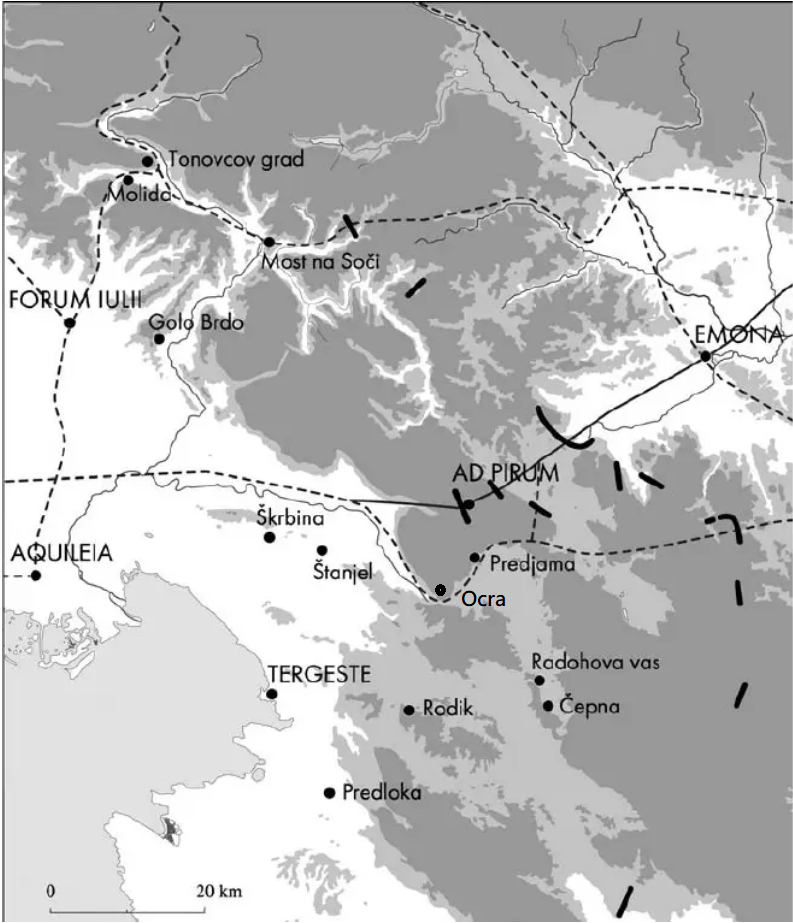

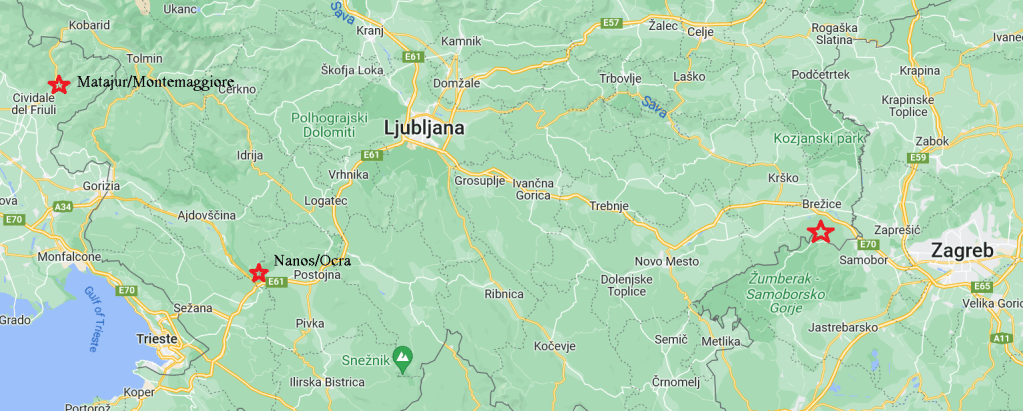

The venerable Thomas Hodgkins confidently identified it as Matajur/Montemaggiore. It is probably associated with the legend due to its proximity to Cividale del Friuli/Forum Iulii, the capital of the first Lombard duchy in Italy. Hodgkins asserted that, contrary to the itinerary described in my earlier post, the Lombards must have gone north from Emona and descended toward Italy through the mountains via the Predil Pass. This route would have taken them past Matajur as they approached Forum Iuliii.

As far I can tell, this was the prevailing wisdom up to the middle of the last century. Narratively, it makes a lot of sense–Alboin climbs up, takes in the view, and immediately swoops down onto the city laid out virtually at his feet. But from a practical standpoint, Matajur is less attractive. The northern routes from Emona are longer, slower, and more difficult. Would a host that apparently included women, children, wagons, and livestock really opt for that?

For a useful visualization, check out Orbis: the Stanford Geospatial Network of the Roman World. It calculates travel routes between points around the Roman world, taking into account the season and preferences for speed, expense, etc. It shows that it’s always faster, cheaper, and more efficient to travel from Emona to Forum Iulii along the Via Gemina via the Ad Pirum/Hrušica pass. In fact, it’s almost impossible to get Orbis generate a different route! We can, therefore, eliminate Matajur as the “King’s Mountain.”

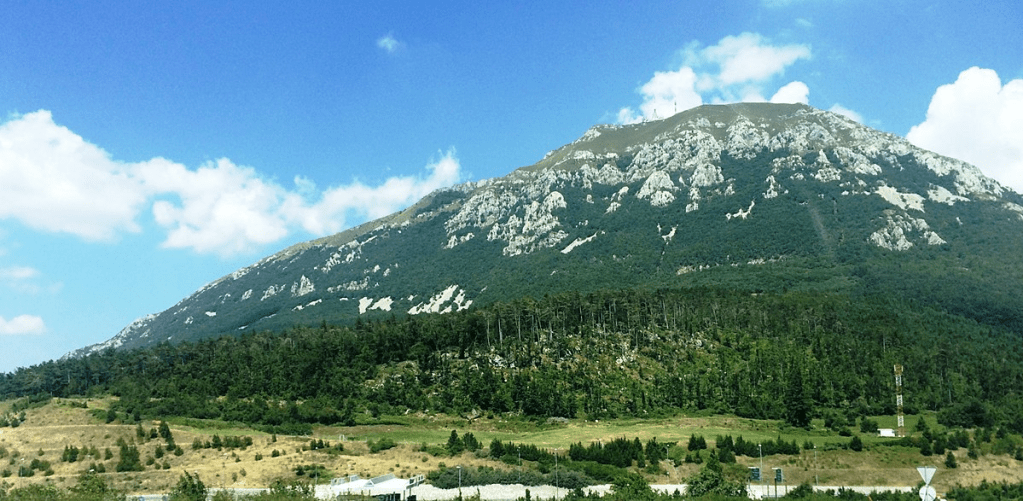

In more recent times, a southern alternative has been proposed–Mt. Nanos, called Ocra in ancient times. This is the mountain that stands above one of the oldest routes connecting Italy to points east. But the road that passed under Mt. Nanos was less direct than the newer route slightly to the north. Additionally, I don’t think it can be fairly said to “touch Pannonia.” On the other hand, on a clear day, Nanos apparently offers views of the Slovenian Littoral, the Adriatic, even as far as Venice!

There is a third hypothesis (which I’ve found only in Slovenian sources,) that proposes a peak of the Gorjanci, a mountain chain in Dolenjska region of Slovenia (although most of the range actually extends across the border into Croatia). If I deciphered the Slovenian articles correctly, they propose that Alboin was actually looking down the Krško plain. This argument depends on the fact that, in the mid-6th century the border of Italy lay somewhere east of Alps in what is now Slovenia. On the plus side, this area is geographically contiguous with the Pannonia, which would explain the oddly specific detail of the wild oxen cited by Paul. On the downside, I doubt Alboin could have seen “Italy” from anywhere in the Gorjanci. Still, an interesting hypothesis.

Alas, the most likely solution to this puzzle is that there never was a King’s Mountain! Paul the Deacon wrote long after the events in question, and as a Benedictine monk, there’s a decidedly Christian flavor to his work. At the time, erudite authors where expected to sprinkle their writing with literary tropes and biblical allusions. It’s now generally accepted that the anecdote of Alboin climbing the mountain is one of these, possibly a reference to the story of Moses climbing Mt. Nebo. The parallels are clear; like Moses, Alboin is a man at the head of a wandering nation. In Paul’s version, the Lombards are cast as God’s chosen people and Italy as the promised land. There may also be a bit of dramatic foreshadowing in the metaphor, since Moses was permitted to see the Promised Land, but not to enter it. Likewise, Alboin leads his people into Italy, but he does not get to enjoy the spoils for long.

If you are interested in learning more, I highly recommend this video produced by the fine folks of La Fara, a group which specializes in historical reconstruction. I’m happy to support their ongoing projects, and they were generous enough to answer my queries on this topic with an excellent video. They do a lot of public education on the Lombard period, so I encourage anyone to check out their youtube channel and support their work. They have lectures on almost any topic you can imagine relating to the era, dramatic renditions of surviving Lombard legends, even a few early medieval cooking videos!

Despite all this, the legend does make a brief appearance in my manuscript…although it doesn’t involve a mountain, per se! Instead, I have Alboin and Rosamund take a quick detour up onto the plateau roughly above Ajdovščina, which is now a paragliding area. While it’s not technically a mountain, it’s still a pretty dramatic spot, and I think it should offer a good view along the upper Vipava valley toward Italy. On paper, it makes sense, but I’m hoping to get out there myself this summer to see how it feels in person. If it doesn’t seem right, I’m open to moving the Lombards’ path south to Mt. Nanos or even to striking the scene entirely, especially since it’s almost certainly ahistorical. Still, I feel compelled to at least nod to this iconic element of Alboin’s legend.

As you can probably tell, I’ve spent quite a lot of time thinking about all this–too much time, as it happens. It’s a good example of something I’ve experienced quite a few times with this manuscript, a frustrating phenomenon you might call “research paralysis.” There is such a thing as too much research, and after a while (for me at least,) it can descend into a procrastinatory doom loop.

I’ve spent the last few weeks trying to figure out what Rosamund might have encountered as she made the journey to Italy. What path did she follow? Who lived in the lands she traversed? What towns and fortresses were occupied and which were already defunct?

And yet, when I finally–finally–forced myself to sit down and write, I found the words weren’t flowing. It’s always a distressing experience when a scene won’t write. I usually end up slugging away at it for longer than I should, even though past experience has taught me that, when the writing isn’t going well, it’s usually because I’m working on something that doesn’t need to be written!

It took me almost three weeks to come to that conclusion this time around. The fact of the matter is that Rosamund doesn’t have much to do during the march. Even if I could invent a few incidents to spice up her experience along the way, the important part of her story unfolds after she gets to Italy. Better to dispense with the travel in as few words as possible and get back to the meat of her story.

Still, I’m a little sad to leave my early medieval travelogue on the cutting room floor–which is why the research has landed here instead!