Therefore, when king Alboin with his whole army and a multitude of people of all kinds had come to the limits of Italy, he ascended a mountain which stands forth in those places, and from there as far as he could see, he gazed upon a portion of Italy. Therefore this mountain it is said, was called from that time on “King’s Mountain.” They say wild oxen graze upon it, and no wonder, since at this point it touches Pannonia, which is productive of those animals….

Paul the Deacon, History of the Lombards, Book 2, ch. 8 (trans. William Dudley Foulke, 1907, ed. Edward Peters 1974)

In this short passage, Paul the Deacon describes the migration of the Lombards into Italy. It seems straightforward enough. We know the journey’s starting point: Pannonia. We know Alboin established the first Italian duchy at Forum Iulii (modern Cividale del Friuli). We have the picturesque detail of the oxen-dotted “King’s mountain.” How difficult could it be to deduce a path that connects these points?

But as ever, nothing is quite as simple as it seems.

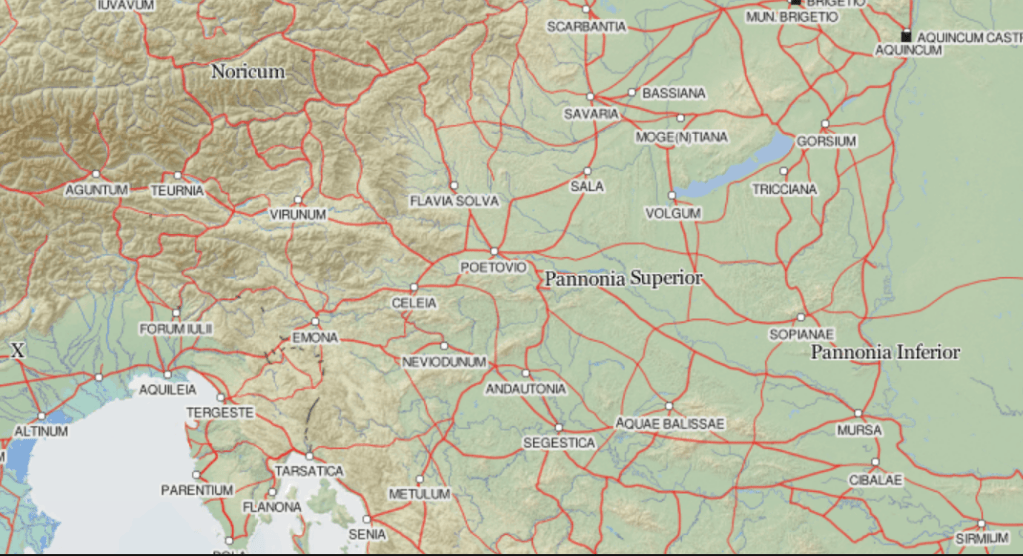

First, a map to give us a lay of the land.

To orient us, Sirmium (former capital of the Gepid kingdom) is in the lower right corner. The relatively blank swath along the right side of the map constitutes the presumed no-mans-land between Lombard and Gepid territories prior to the Lombard migration into Italy. Aquincum in the top right corner is modern Budapest and was part of the Lombard kingdom in Pannonia. They occupied the area marked Pannonia Inferior as far south as Mursa and (at times) Cibalae, all of Pannonia Superior at least as far west at Poetovio, and areas adjacent to the top of the map in the direction of modern Vienna.

The map above depicts the Roman road system. Of course, by the mid-6th century, the roads were no longer well-maintained, but they had been laid out with an eye to efficiency and terrain. I have no doubt the routes were still in regular use, even if the roads themselves had fallen into disrepair.

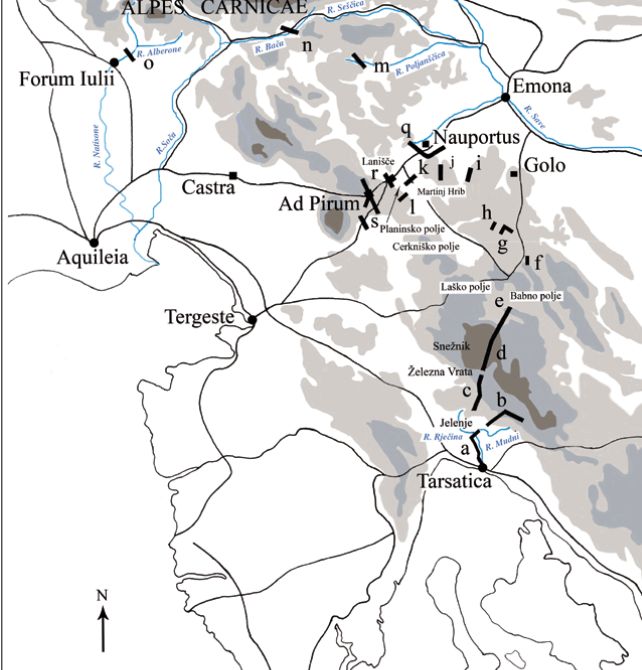

The other major factor to consider are the mountains. The Julian and Dinaric Alps shield the northeastern corner of Italy, but further to the south, the frontier is more permeable. Since antiquity, traffic between Italy and the Danubian Basin funneled through several important passes. One of the oldest of these was at Ocra (modern Mt. Nanos). Nanos/Ocra itself was said to constitute the southernmost peak of the Alps. Later, another road was constructed a little to the north, through a pass called Ad Pirum. This route saved a day’s travel. It immediately became the main highway between Aquileia and Emona.

To determine the Lombards’ route, it makes sense to consider those who came before. As the saying goes, past practice predicts future behavior.

The Lombards were not the first people to migrate into Italy from Pannonia. The Romans’ alpine fortifications were apparently abandoned with the advent of Alaric and the Visigoths around 400. Attila and his Huns soon followed. Only 100 years before the Lombard migration, the Ostrogoths also marched into Italy from the east, following the roads up from Pannonia, probably via Sirmium and Emona. They faced their first major battle on Italian soil near the Isonzo (Soça) River.

It seems logical that the Lombards would have followed roughly the same path as the Goths. But corollary to the question of how they came to Italy is the question of what they would have seen along the way. The area along their likely path had been devastated numerous times in the late antique period. Many invaders, not least the Goths and Huns, overran the defense system, and it is likely that most–if not all–fortifications had been abandoned. At best, they were much reduced from their former state.

Coming from Pannonia, their first major stopping point was probably Emona, near the site of current Ljubljana. This area was an alluvial plain and probably quite wet and boggy. Archeological evidence indicates Emona was defunct by the mid-to-late-6th century. No doubt some civilians still clung on, and Slavs were also migrating into the area, but there’s little evidence of continued occupation in the old city. The area probably wasn’t even called Emona anymore. Sometime in the previous century, the area had been dubbed Ad Emona (“at/near Emona”), which gradually morphed into Atemona. In the following decades, the incoming Slavs transformed the name again, so that it is recorded as Atamin(e) in the Ravenna Cosmography (c. 700). My best guess as to the name when Rosamund passed through is Atemona.

The Lombards would have probably followed the Via Gemina, the Roman road that linked Emona to Aquileia. They would have passed another deserted settlement at Nauportus (modern Vrhnika) which had been an important river port. Around this area, they would begin to observe the remnants of the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum, the network of forts, towers, walls, and gates at strategic points along the eastern frontier. You can still visit the foot of a Roman watchtower on a hillside near Vrhnika–the ruins might have been standing to a greater height in the 6th century.

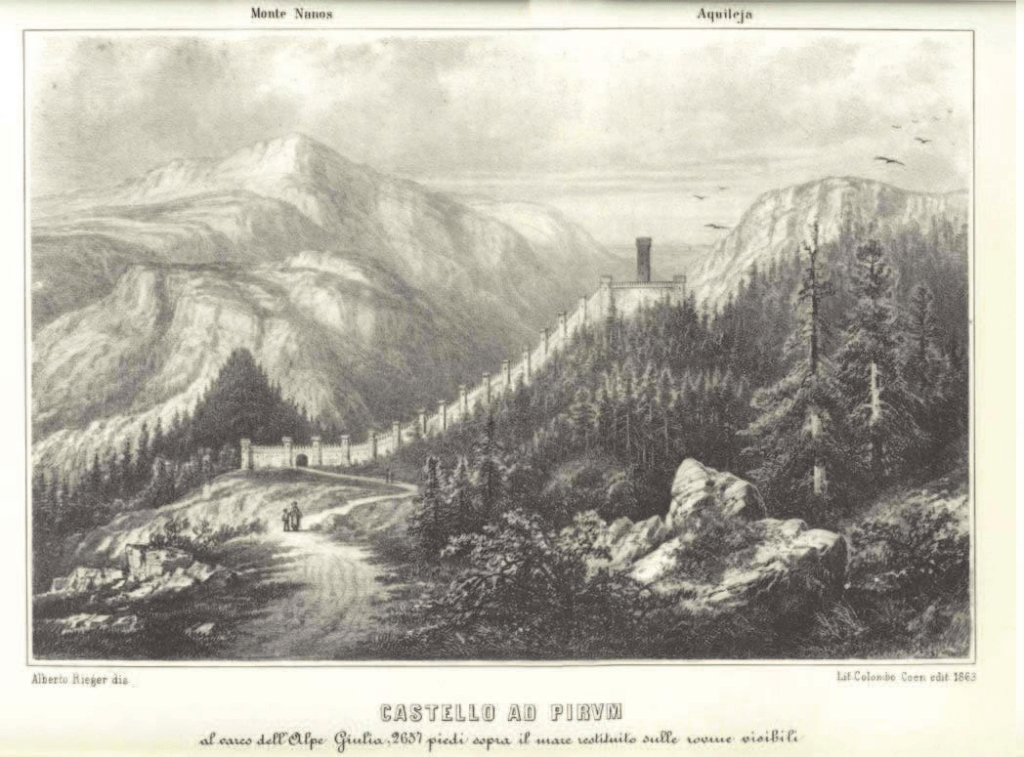

From Nauportus, the road rose to the fortified pass at Ad Pirum, another part of the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum. In its heyday, Ad Pirum would have regularly housed hundreds of soldiers. The Claustra Alpium Iuliarum was largely destroyed by the time the Lombards arrived, but the remnants of Ad Pirum are still visible today near the postal station east of Podkraj, Slovenia. You can check them out on google streetview. There’s a neat 3D visualization of how it may have looked in its heyday here. No doubt Rosamund could have observed the ruins too.

The road then wound its way through a gap in the limestone plateau before opening onto the Vipava Valley. The Vipava (latin Frigidus) flows through a lovely valley. The river itself is quite unusual for its delta source (it arises from numerous springs), which I imagine was probably quite marshy in Roman times. The road followed the river down the valley until it joined the Aesontius at Pons Sontii.

The Via Gemina continued east toward Aquileia at that point, but Alboin apparently decided to turn north–at least temporarily–to secure his eastern flank by establishing his nephew in the duchy of Friuli.

All in all, this is not a terribly long journey, but the travel time was probably extended due to the the makeup of the group, which included significant numbers of women and children, people on foot, wagons, and herds of animals (presuming, of course, that Paul the Deacon’s description is accurate, which many historians dispute with fair cause.) I think it’s likely they would have prepared fortified camps each night, possibly in the form of wagonburgs, which was a defensive arrangement utilized by various barbarian peoples. It involved literally “circling the wagons.” The Franks were known to partially bury the wagon wheels to decrease the space beneath the carriage. Defensive ditches might also have been used. Wagons could be useful in other ways. Spears could be loaded into them point-out to deter bandits. In a pinch, the heavy disk wheels could be detached and rolled downhill into attackers.

The Lombards seem to have enjoyed a relatively uneventful journey, however. Almost all accounts describe how they entered Italy unopposed. Even assuming a pause after the first stage around Emona, it probably didn’t take more than a month or two, putting them safely into Italy by midsummer 568.

Now all that remains is to identify the famous “King’s Mountain,” a debate I will save for another post….

Pingback: A View for the Ages? Part 2 | A Queen's Cup