This year, Alboin, King of the Longobards, leaving and burning all of Pannonia, his fatherland, with all his army, with wives and all his people occupied Italy in “fara”; and there some were killed by illness, some by hunger, and others by the sword.

Marius Aventicensis,Chronicon, 569.1 (580)

Writing circa 580, the chronicler Marius Aventicensis recorded that the Lombards arrived in Italy in 569. This is one of the earliest attestations of the Lombard migration and a great example of how scant and tantalizing the sources from this period can be!

Marius Aventicensis says that the Lombards undertook their migration “in fara”–a term which he apparently presumed his audience would understand. In decades past, the word has been the topic of sometimes strenuous debate among historians and philologists. More recently, a groundbreaking paleogenetic investigation has shed new light on this controversial subject, and it is this data that informs my own answer to the perennial question: what exactly was a fara?

First, it may be useful to recount what we know of the the fara from the sources. The term is first recorded, not among the Lombards, but in the 6th century Burgundian legal codes. There, reference is made to the faramanni–the men of the fara. There is the impression that it must be a unit of social organization among the Burgundians, but beyond that little can be said.

Fara next appears in the Edict of Rothari, the first written compilation of Lombard law, issued in the 7th century.

A freeman can go where he wishes together with his fara…

Edict of Rothari, chapter 177

Finally, we have perhaps the most famous reference to the fara:

When Alboin without any hindrance had thence entered the territories of Venetia,…he began to consider to whom he should especially commit the first of the provinces that he had taken….he determined, as is related, to put over the city of Forum Iulii and over its whole district, his nephew Gisulf, who was his master of horse…a man suitable in every way. This Gisulf announced that he would not first undertake the government of this city and people unless Alboin would give him the “faras,” that is the families or stocks of the the Langobards that he himself wished to choose…

Paul the Deacon, History of the Lombards (trans. William Dudley Foulke 1907, ed. Edward Peters 1974)

Paul the Deacon thus provides us with a seemingly definitive answer to our question–among the Lombards, fara simply means “family” or “lineage.” Perhaps in his own time, this was true, but he wrote his history centuries after the migration (and, incidentally, the setting of my story). Lombard culture had undergone major changes in Italy, and the fara of the 8th century might not perfectly reflect the fara of the 6th century.

Here, it is useful to turn to philology. The general consensus is that fara comes from a Germanic root word that implied movement or journeying and is related to the German word faran (to move, to go, to travel) and the English verb fare (to travel). Thus the Lombard word fara implied a group that traveled together. From the fact that Gisulf requested certain faras to serve as his armed forces in the first Lombard duchy, we can presume that the faras were also units of military organization.

We can glean further overtones from a letter from Pope Gregory I (540-604) in which he refers to several Lombard faras, although he calls them by the Latin term familiae (“families”). This gives us another clue as to their nature in the late 6th century. The Latin term chosen by the pope gives us to understand that they were, perhaps fundamentally, groups based on bonds of kinship. Certainly this element of fara persisted into Paul the Deacon’s era.

Languages are living things, and meanings morph over time. The word fara was no exception to the rule. What probably began as a term for a mobile military unit organized around family relationships gradually transitioned to a term for a settlement unit once the Italian kingdom was established. The evidence here is the proliferation of Italian place-names that incorporate the word fara/farae. Some of these names still implied communities of descent, but gradually, fara came to represent the settlement area in a general sense, i.e. the property the group possessed, not the group itself.

This is all very interesting, but passing references in the sources and etymology can only take one so far toward a full understanding of what was almost certainly the fundamental unit of social organization among the migration-period Lombards. But very recently, a multidisciplinary study led by Patrick Geary of Princeton University has shed new light on the 6th century fara. It centers on two necropoli–one on Hungary and one in Italy.

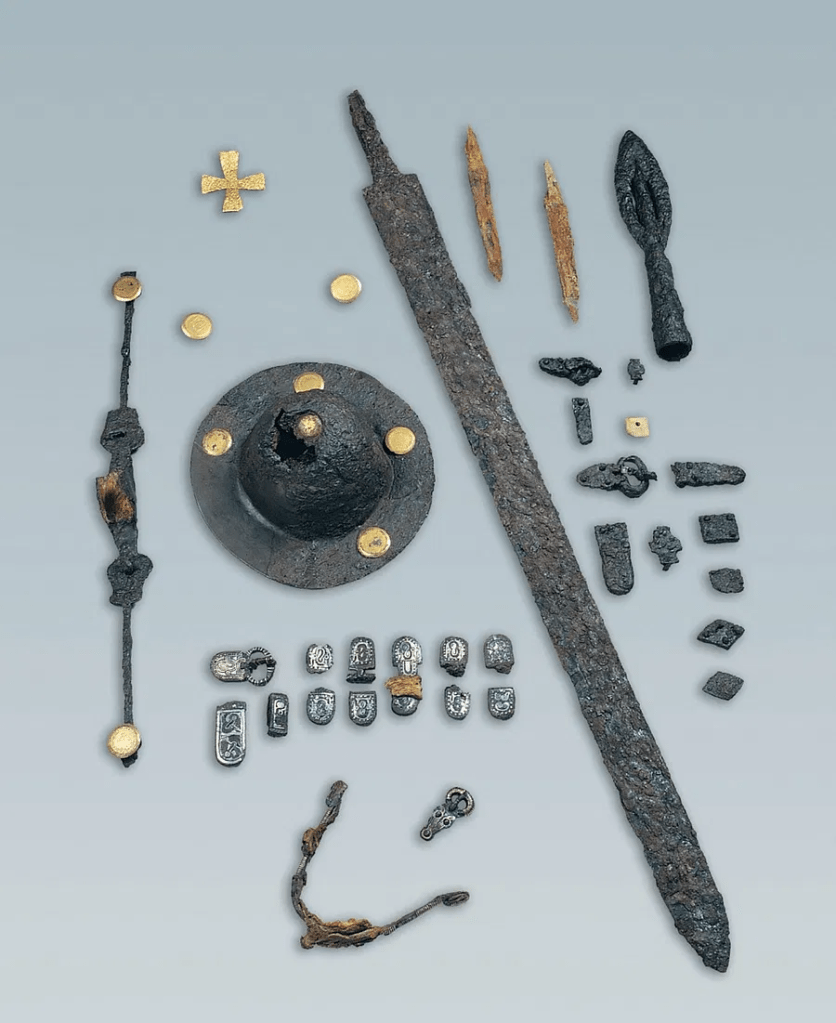

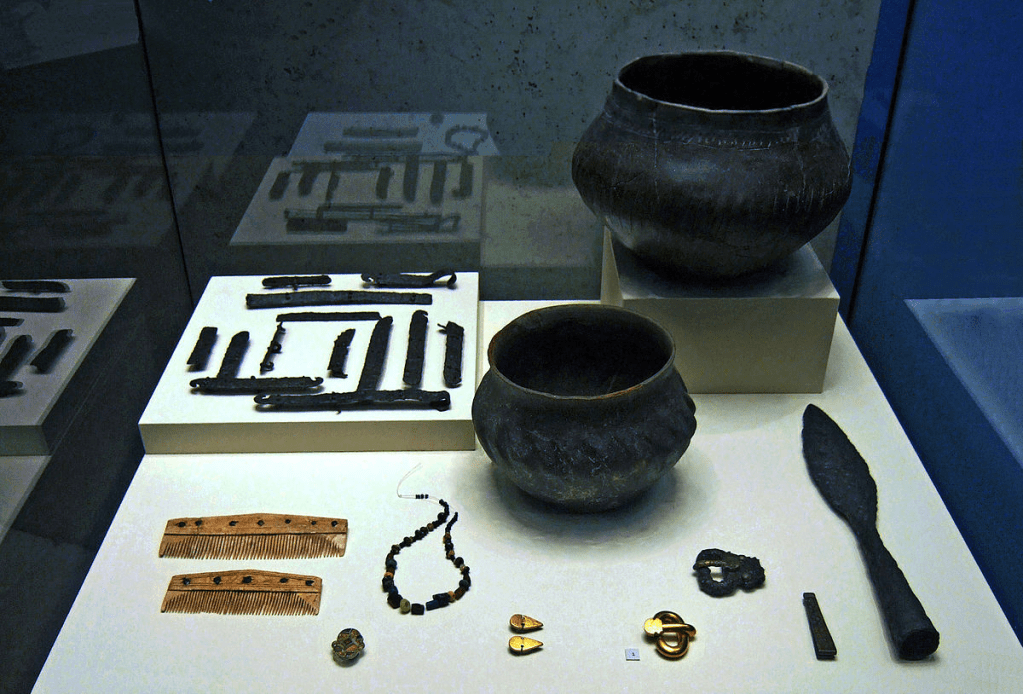

The Szólád necropolis, discovered in Hungary near Lake Balaton, was occupied by a population tentatively identified as the Lombards for approximately one generation prior to 568 (the date of the migration into Italy). The Collegno necropolis near Turin, attributed to the Lombard settlers, dates to the period immediately subsequent. Thus, these two cemeteries potential represent individuals who actually participated in the migration and their immediate descendants. The comparative paleogenetic analysis of the remains, as well as more traditional archeology (concerning grave construction, material remains, artifact deposits, etc.) have been combined in a groundbreaking investigation that explores whether genetic data can shed light on historical events. The article (highly recommended!) is available here.

The comparison of the bodies from Szólád and Collegno are indeed illuminating. In both cemeteries, there appear to be individuals of distinct genetic origins. The first group bear similarities to modern northern and central Europeans, and based on strontium analysis, at least the first generation were newcomers to the area. The remaining bodies in the necropolis are genetically more similar to southern Europeans and most of them were born quite close to where they were buried. The burials of the “northerners” occupy privileged positions in the necropolis, while the “southerners” are more peripheral. The “northerners” graves are more richly furnished, and the most important men (judging by grave position) are armed, as opposed to their “southern” neighbors. Additionally, the diet of the “northerners” contained more animal protein and they were generally healthier. In both cemeteries, many of the core burials represented an ancestor and several generations of his male descendants–an agnatic, patrilocal clan–and in neither was there evidence of intermarriage between the “northern” and “southern” populations. The clear implication is that agnatic clans settled in both areas, constituting a privileged, armed elite that ruled over a more impoverished indigenous population.

All this begs the question–do the “Lombard” men buried in Szólád and Collegno actually represent a fara? The scientists and historians are wise to be cautious, but I’ll go out on a limb and say yes! Of course, firm answers await surveys of additional necropoli, but for now, this is as complete and impartial a picture as we can expect. Thus, for the purposes of my story, a fara is an agnatic, patrilocal clan whose members travel and fight together. During the time of the migration, they travel to Italy as organized units, together with their households, retinues, and dependents. This is a society that is fundamentally tribal, which probably still preserved certain traditions and military/social structures that predated prolonged contact with the Roman world. For a society in which “the people are the army,” it only makes sense that the family is also a military unit! This is the “flavor” of Lombard society at the time of my story, and it is what I try to represent in my writing, without undue romanticism.