I had to invent a mother for Rosamund (whose own existence is up for debate in certain quarters, an interesting topic for another day). But what of Alboin’s maternal line? He, at least, is a historical figure, so he must have had a mother.

There are two theories as to her identity. The first–and most prevalent–is that she was a princess, the daughter of the last independent king of the Thuringians. This would make sense. Both Alboin and his father seem to have had some sort of of Thuringian connection.

So far, so simple. But as ever, when you pull on random a thread from this period, a whole host of fascinating stories tumble into view.

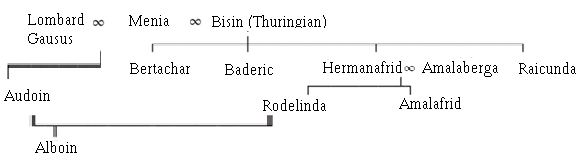

The story really begins with Alboin’s paternal grandmother, a woman named Menia. Interestingly, she is the first named ancestor of Alboin’s lineage–the Gausi family. The Historia Langobardorum names Menia as a onetime queen of Thuringia, the wife of King Bisin. Presumably, she was the mother of Bisin’s four known children: three sons and a daughter, Raicunda, who would marry King Wacho of the Lombards (discussed here.)

The children of Menia and Bisin

Bisin was dead by the first decade of the 6th century, so the widowed Menia apparently joined her daughter among the Lombards. She remarried a Lombard man of the Gausi family and had a son–Audoin. It’s unclear to me whether Menia was a Lombard by birth or some other ethnicity. Whatever her extraction, her former queenship brought her special status and gave her Gausi Lombard descendants a claim on power. Her new son, Audoin, was half-brother to the Lombard queen as well as the kings of Thuringia. He was probably attached to Wacho’s court and later became the legal guardian of Wacho’s minor son. This trusted position allowed Audoin to seize the throne for himself when the young king died (discussed further here).

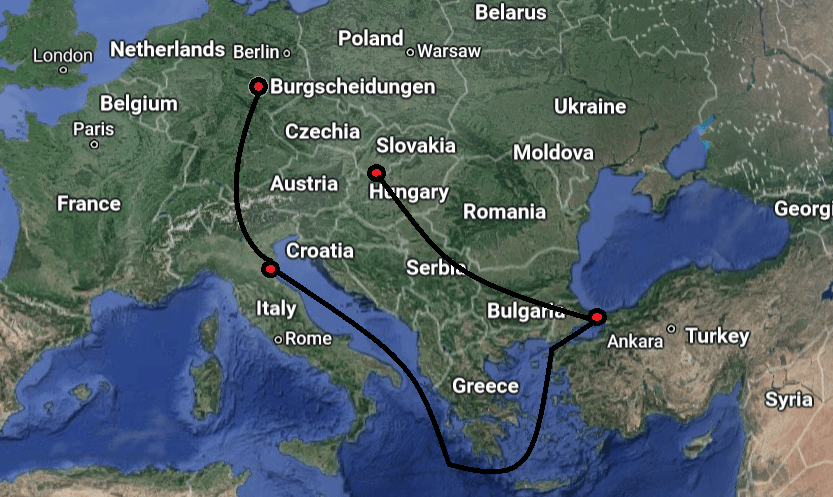

Audoin wasn’t Menia’s only son with a penchant for power plays. Her sons by Bisin battled each other for supremacy until one, Hermanafrid, succeeded in eliminating his brothers to become the sole king of Thuringia. But he wouldn’t rule for long. According to Gregory of Tours, the Franks defeated Hermanfrid in a major battle near the river Unstrut. Hermanafrid suffered a long fall from a high wall, and Thuringia was absorbed into the Frankish kingdom.

As I’ve described elsewhere, various Thuringian princesses were parceled out as prizes among the Franks. Not so for Hermanfrid’s widow, Queen Amalaberga. She was a Gothic princess of the highest rank, a niece of Theodoric the Great, whose rule in Italy was famed throughout Europe. As the story goes, she was the one who spurred her husband’s ambitions. Amalaberga’s brother was then ruler of the Gothic kingdom. Husband dead, she fled home to Italy with her two children in tow.

Unfortunately, the circumstances which brought Amalaberga’s brother to the throne in Italy served as the pretext for a decades-long conflict with the Eastern Empire–the Gothic War–which would eventually destroy the Ostrogothic kingdom, leave Italy in ruin, and set the stage for the Lombard invasion. Amalaberga and her children found themselves in a warzone. A few years after their arrival in Italy, they were captured and dispatched to Constantinople as hostages.

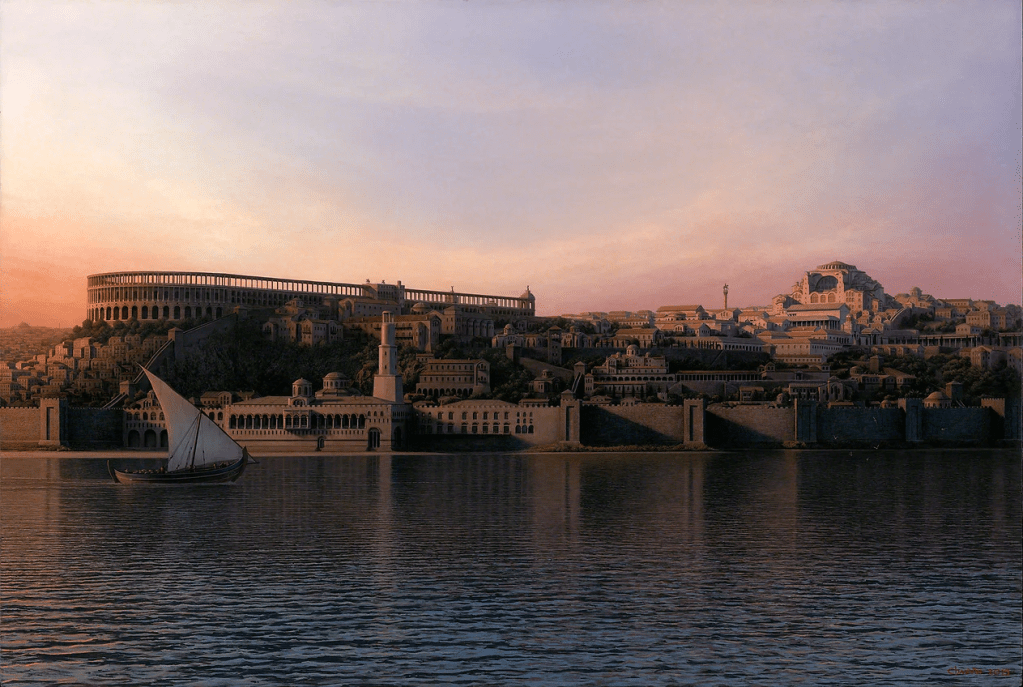

I imagine life was relatively comfortable for Amalaberga and her children in Constantinople. They were valuable bargaining chips due to their status. Previous Amali hostages in Constantinople, including Theodoric himself, received classical educations. Perhaps Amalaberga’s children did as well (if they hadn’t already.) The hostages were close to the imperial court. Amalaberga’s son, Amalafrid, eventually became a general in the emperor’s service. He spent his entire career in the East Roman military. There’s no indication that he harbored any nostalgia for his past. In fact, in an epistolary poem, his Thuringian cousin, Radegund, scolds him for never visiting her or even sending a note (of course, her complaint came too late, for by that late date Amalafrid had already died in Roman service). Meanwhile Amalaberga’s niece, another Gothic hostage, married the emperor’s cousin.

But what of Amalaberga’s other child, Amalafrid’s sister? Procopius, the East Roman commentator, describes her fate but does not name her. The Historia Langobardorum calls her Rodelinda. Sometime after 540, the Lombards became allies of the Eastern Empire. The emperor, Justinian, officially granted them the cities and fortresses of Noricum and Pannonia (provinces which were, in fact, no longer under Roman control). As a token of their friendship, Justinian sent Audoin a gift fit for royalty–Rodelinda. Audoin married her and made her his queen.

Audoin had seized the Lombard throne by his own daring, although he probably owed his position close to the seat of power to his kinship with the former queen Raicunda. Now, through his illustrious marriage, Audoin could lay claim to the vanquished Thuringian kingdom (via Rodelinda and, perhaps, Menia,) as well as the Ostrogothic kingdom of Italy (via Rodelinda/Amalaberga). It’s noteworthy to observe how, once again, power could pass along female lines. Many historians believe that Rodelinda was the mother of Alboin, allowing him to trace his own bloodline through the noble lineages of the Ostrogoths, the Thuringians, and the Lombards. This must have been a major political asset.

Here, it’s a bit easier to see that Audoin was Rodelinda’s half-uncle.

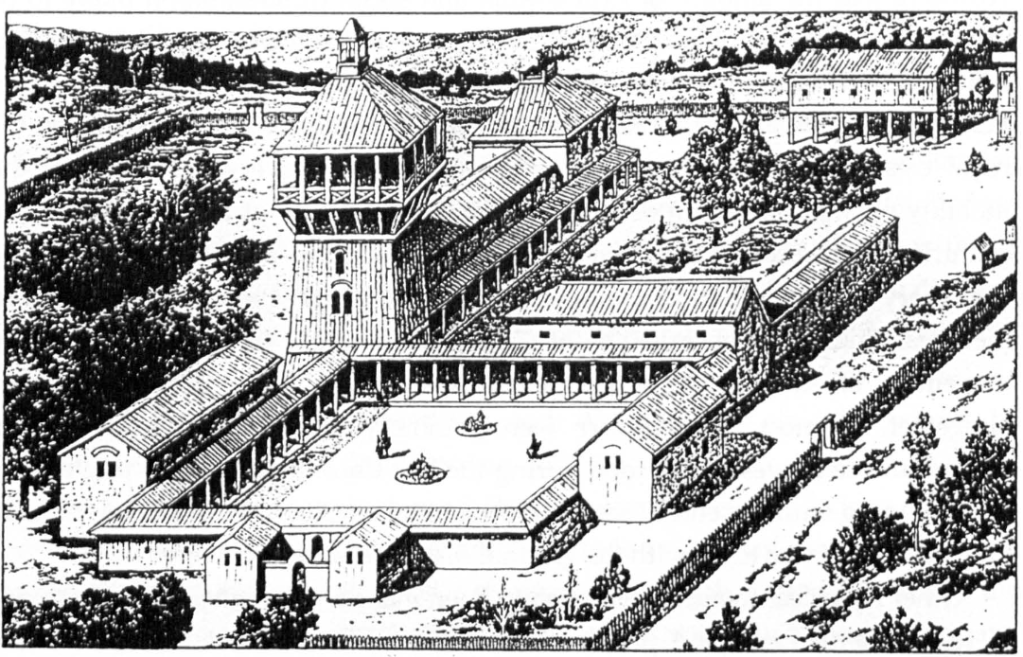

Between the branches of Alboin’s complicated family tree, we can just catch a glimpse of his mother’s rather dramatic life story. Rodelinda would have been born a princess, the daughter of a man riding high in the world. He had eliminated his main rivals to become the sole king of Thuringia. But her father’s seat at Scithingi was no Ravenna or Constantinople (nor even a Toledo or Trier).

In short order, this young girl lost her father and home and fled over the Alps to a world vastly different from the one she had known in central Europe. She probably spent her sojourn in Italy living in intact late-Roman cities and palaces as part of the famously cultured Ostrogothic court. But after only a few years, she and her family were taken captive and transported to Constantinople, one of (if not the) greatest Western city of the day. She would have been exposed to the staggering splendor and ceremony of the East Roman court. But her fate was no longer in the hands of her kin. However well kept, she belonged to the emperor, and when the time was right, he sent her to the hinterlands to marry a man she did not know. What would this woman–who’d seen Ravenna and Constantinople–have made of the plains of her kinsman-husband’s country? Would it have felt like a diminution? Or a homecoming?

While few historians doubt Rodelinda’s betrothal to Audoin, some question whether the marriage ever took place. Others grant that Rodelinda was Audoin’s queen but debate whether she was actually Alboin’s mother. The sources are unclear and sometimes in conflict. The trouble here seems to hinge on whether one believes Alboin fought the Gepids in the battle of Asfeld and, if so, how old he must reasonably have been at the time. I discuss my own opinion on the subject and Alboin’s age here. I tend to suspect that his role at Asfeld is a trope added to the saga account of his life after the fact, which means that he could have been born later than generally assumed and Rodelinda could well be his mother.

For those historians who believe the dates require another woman to be Alboin’s mother, there are several options. Some simply say we cannot know her name or origins. She might have been Audoin’s wife before his marriage with Rodelinda. The Hungarian archeologist István Bóna said she was a Bavarian princess. I’m not quite sure what, if any, evidence backs this up.

To my mind, the fact that Alboin had a Thuringian connection through both his mother and his paternal grandmother makes a lot of sense. We know that there was a powerful Thuringian contingent in the migration Alboin eventually led into Italy. Perhaps they were drawn to Alboin’s banner partly as a result of his heritage. His connection with Theodoric’s family, via his mother, may have also encouraged the Ostrogothic element still present in Italy to join his forces.

My only reservation in wholeheartedly endorsing Rodelinda as Alboin’s mother is that I have some trouble squaring the relative ages of Menia, Amalaberga, and Rodelinda. Given the likely dates of their various marriages, one of these women must have produced a child surprisingly late in life–nothing a bit of hand-waving can’t fix.

Despite the inevitable uncertainties, in my story Alboin is the daughter of Rodelina. She had quite the story to tell. Did she share it with her son? Did he perceive any symmetry between his mother’s experience as an exile, political hostage, and queen and that of his wife, Rosamund? How would that color his attitude towards her?

Rodelinda does not appear as a living character in my story, but her influence surely lingers in her son, who keeps her memory alive as a matter of good politics and filial loyalty. His perception of her tumultuous life story colors his expectations of Rosamund, and (hopefully!) lends him a more nuanced and human character.