Cunimund (and possibly Thurisind) supposedly minted silver coins (half-siliqua, quarter-siliqua) in the style of Roman currency in Sirmium. The Ostrogoths first restarted the Roman mint in Sirmium when they occupied the city between about 505 and 535. Coins from the period of Ostrogothic occupation commonly bear the names of the then-ruling Roman emperor on the obverse, and the monogram of Theoderic, the Ostrogothic king, on the reverse. They definitely struck coins in the name of Anastasius (491-518) and Justin I (518-527), and it is possible they minted coins during the first years of Justinian’s rule beginning in 527.

It appears minting operations ceased for a time during the transition from Ostrogothic to Gepidic control of the city, about 527-535. The exact date of the Gepid takeover is not definitively known, but the earliest possible date for resumption of minting activity would be around 536. Either Thurisind or Cunimund may have struck coins in the name of Justinian, and Cunimund may have struck coins in the name of Justin II (565-576) for a brief time before the destruction of the Gepid state in 567.

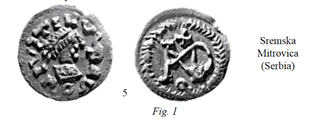

Gepidic-era coins were (and are) sometimes attributed to the Ostrogoths and vice versa. It’s easy to see why. The coins of both periods share a similar design, with the portrait and name of an emperor on the obverse and a monogram on the reverse. But I think there’s a decent argument to made that Cunimund “adapted” Theoderic’s monogram to suit his own name. His monogram is ringed by a laurel wreath instead of an inscription. The cross and the moon are still present; these are probably symbols representing Christianity and the state, respectively. The other alternative is that “Cunimund’s” monogram is just a modified or simplified version of Theoderic’s and that none of these coins date to the period of Gepid occupation at all.

The Gepid-era Sirmium mint may have struck coins in other designs as well. All of them bear the name of the emperor on the obverse. The reverse designs vary, but may include the three crosses of Golgotha (sometimes also referred to as “the veneration of the cross” design,) a portrait of an angel (possibly Michael the Archangel, who I’ve tentatively named “Mikahel” in Gothic?), or a cross with a “C” (for Cunimund?) and a star on either side.

There are a lot of challenges in dating and attributing the coins of this period, not least because there are forgeries in the marketplace and even in museum collections. There has been more collector interest in “barbarian” coinage of late, and unscrupulous individuals are always ready to meet demand.

Most of the numismatic finds come from the southern part of Gepid territory, so it’s likely these coins only circulated as currency in Pannonia Sirmiensis. Sirmium had long been an important trading city at the crossroads between east and west, north and south. Although diminished by several centuries of conflict and contraction, it would still have been an important marketplace and the gateway to the western empire.

There was also still a Roman population in the area around Sirmium. Even though they probably weren’t much distinguishable from their “barbarian” neighbors by the mid-6th century, they may have been accustomed to trading, being compensated, and paying taxes with currency.

Beyond Pannonia Sirmiensis, in the Gepidic heartland along the Tisza, coins were valued as markers of wealth and status. They were fashioned into pendants and brooches and other jewels worn by elite women. Some probably ascribed apotropaic properties to them. Like other “barbarian” states, the Gepids had a complex relationship with the Romans to their south. They admired, coveted, and depended on the empire’s wealth. Sometimes, they sought to imitate it–through operation of a mint, for example. They adopted and adapted certain institutions to underline their own power and significance; the symbols of Rome were to some extent, universal markers of power.

And yet, they were careful to maintain a certain distinctiveness in contrast to the empire. Their elites were Christians, but staunch Arians rather than Nicene Catholics. This was probably less a matter of deeply held doctrinal disagreement, and more a mark of cultural distinction. There is some evidence that the Gepids did not occupy the ruins of Roman towns and villas in their territory. They built their own settlements using their preferred materials. They minted coins bearing the names of their kings, even though they had limited use as functional currency. They wanted to be like the Romans, yet different from them. This is my interpretation, at least.