A final figure of note must be the queen. Fundamentally, a queen was simply the wife of a king. She need not be his only official sexual partner. Kings of the early medieval period sometimes kept recognized concubines. Some even had multiple wives. Regardless of personal arrangements, the queen took precedence over the other women in the king’s orbit.

In the 6th century, the position of queen was essentially personal. She was not anointed in a special ceremony that we know of. A woman became queen when she married a king–provided that was her husband’s will. But marriage itself was less “hard and fast” in those days. In a Christian context, marriage was not a sacrament, and divorce was no taboo in the “barbarian” traditions. The position of queen was, therefore, inherently precarious.

The case of the Frankish king Chlothar (died~560) and his wives provides some insight. Chlothar had a reputation of lasciviousness and was, apparently, a bigamist. He had at least 6 consorts. According to one infamous story, one of his wives complained that her sister did not have a husband and asked Chlothar to find a suitable man for her to wed. Chlothar agreed and went to inspect the young woman. When he returned, he declared that he had found her ideal match–himself!

At various times, Chlothar was also married to Saint Radegund (discussed here) as well as the widow of one of his brothers, whom he had killed in classic Merovingian style. He also kept many concubines, although we know only a few by name. One of them was Waldrada (the daughter of Lombard king Wacho, discussed here). Only some of Chlothar’s consorts were considered queens. They seem to have carried the title at his discretion, but it appears there was only ever one queen at a time

A queen’s primary role was to produce a male heir or heirs. If she failed to do so, she could be put aside and replaced. Her authority derived from her intimate relationship with the king, access to royal and personal wealth, and authority/influence over her children. Queens secured their positions by promoting favorites at court, gathering allies, and undercutting enemies.

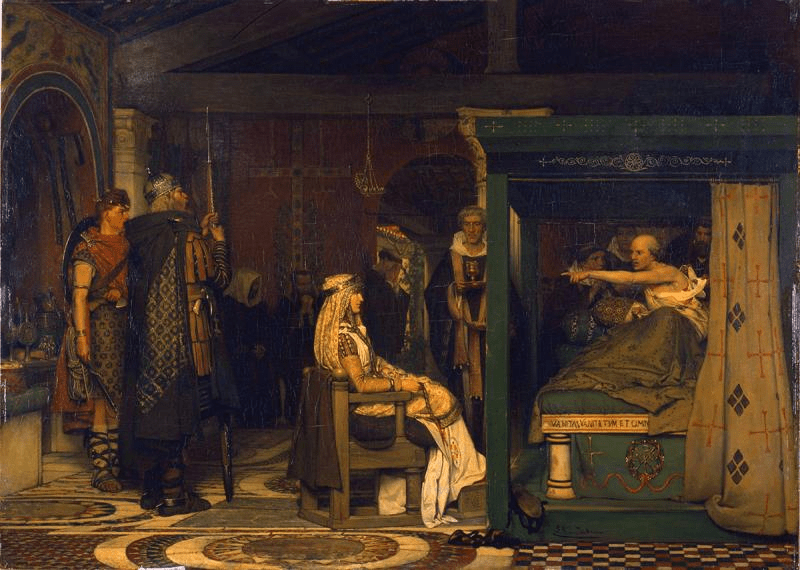

A queen needed money to furnish and equip a household fit for royalty. Certainly, they had access to the royal chamber–and the royal treasure within.

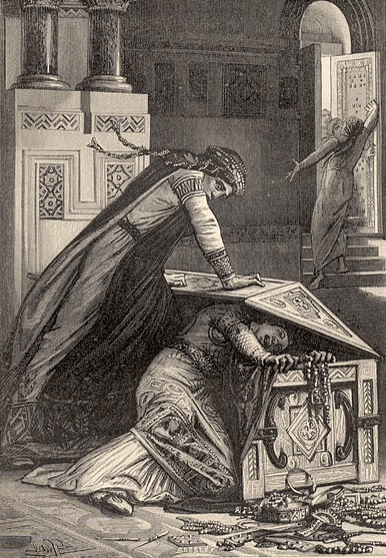

Many also enjoyed substantial personal wealth. Most queens received dower property from their husbands when they married, and they kept the revenues from these properties. For example, when Frankish queen Fredegund’s daughter was sent to marry, the convoy was so loaded with treasure that the courtiers became concerned. Was the royal treasure completely depleted? Fredegund assured them that the girl’s gifts all came from the personal wealth she had amassed as queen. One wonders if this was cold comfort to the jealous courtiers, but it does give a sense of how stupendously wealthy an ambitious queen like Fredegund could be.

The Queen was often the first to take control of the royal treasure when her husband died. This could give her substantial political influence. Many queens became most powerful during the regency of their underage children. Other widowed queens became targets. Seizing and marrying the queen often meant capturing the royal treasure–and the crown itself.

I do think there is precedent for the queen taking an active role at court. In my story, the queen and the domestic ministers (steward, butler, etc.) work hand-in-glove because the Queen stands in the king’s place when he is absent, which is a frequent occurrence. Many queens of this period had more formal education than their husbands. They were responsible for overseeing their children’s education, so some (perhaps most) could read in write, even in multiple languages. A queen also needed to be financially literate to protect her own interests, as well as those of the king and her children.