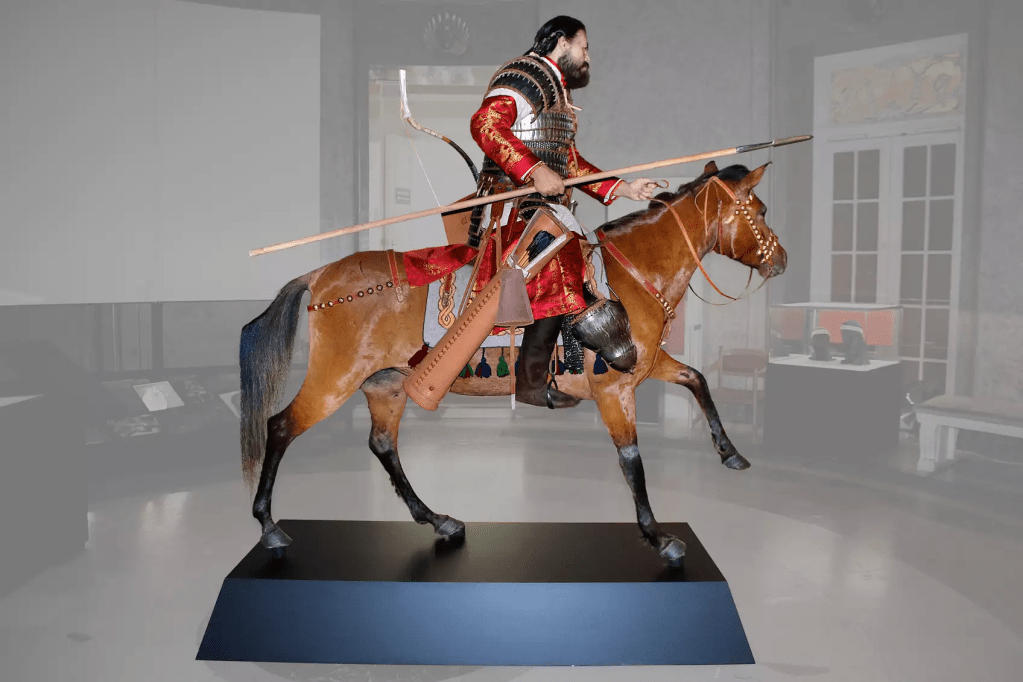

The Gepid kingdom ultimately succumbed to an alliance between the Lombards and the Avars. The Avars were relative newcomers on the eastern European scene. Their origins have long been shrouded in mystery, but the prevailing theory proposes that they were refugees from the Rouran Empire of the Mongolian steppe, which had been overthrown by the Göktürks. For over a thousand years, their true origins were a mystery waiting to be solved.

Amazingly, a recently published multinational study of Avar archeogenetics has pulled back the curtain, revealing that the Avars traversed more than 5000 kilometers–from Mongolia to the Caucasus– in only a few years. Ten years after that, they replaced the Gepids in the Carpathian basin. This was the fastest documented long-distance migration in human history. Incredible stuff!

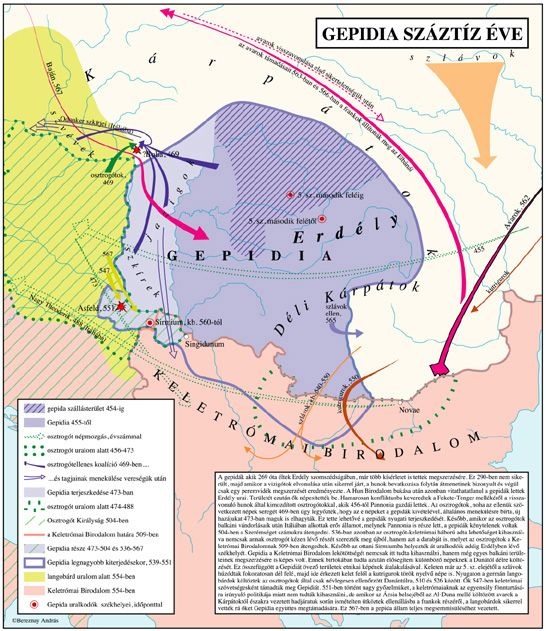

So why did the Avars travel so far, so fast? Possibly because the Göktürks–who had overthrown their empire in the east– were in pursuit. According to the martial customs of the steppes, once they caught up with them, the Avars would be devastated and subjugated. The Avar khagan (king), Baian, needed a safe harbor. Around 562, he petitioned the Eastern emperor, Justinian, for lands within Roman territory, but negotiations collapsed. No doubt the Avars attempted to break through the Gepid defenses along the lower Danube to reach the Pannonian basin, but those efforts were also in vain.

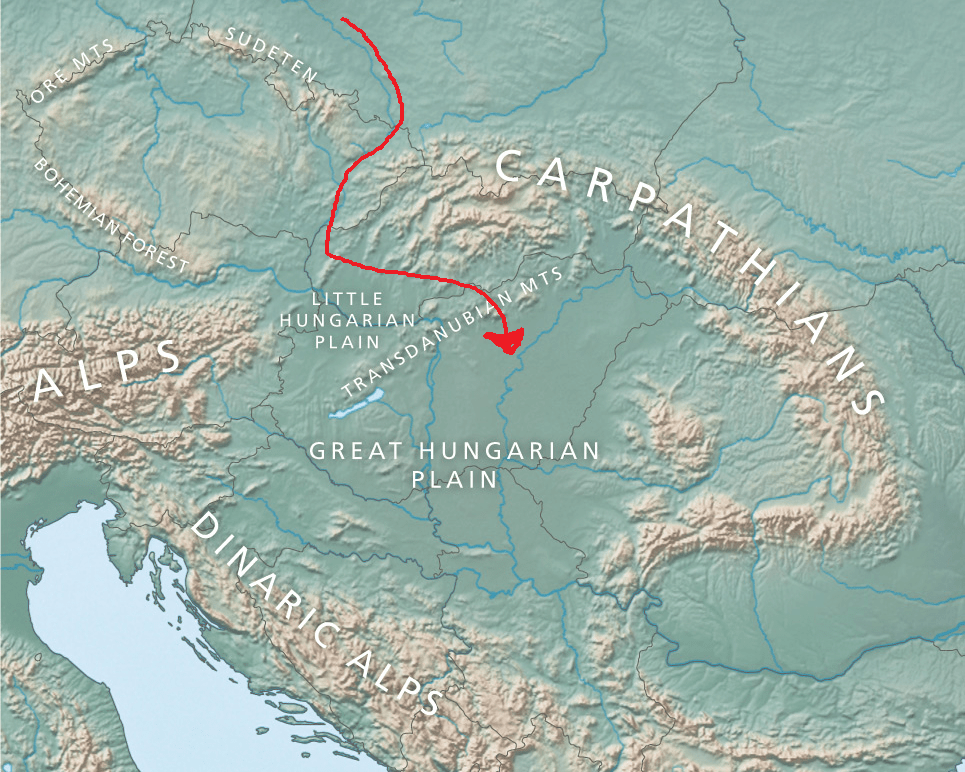

Despairing of a southern route into the Carpathian basin, Baian led his armies north to try his luck against the Franks. Sigebert I, the king of Austrasia, repelled the Avar attack around 563. Baian returned to the banks of the lower Danube, but mounted a renewed assault along the same route in 566. This time, they met with greater success, won a victory against the Franks, and even captured King Sigebert. But winter was setting in, and according to a later East Roman source, the Avar army was “starving.” Sigebert and Baian entered into peace negotiations. Baian promised to withdraw “in three days” if Sigebert provisioned the Avars–a proposal the Frankish king hastily accepted.

In 566, the Lombards and Avars shared a common enemy–the Gepids. The Lombards and the Gepids were unfriendly neighbors who had engaged in on-and-off war for decades. The Avars wanted to occupy the lands of the Gepid kingdom, with its strong natural defenses and a landscape well-suited to animal husbandry. An alliance between Alboin and Baian made good sense.

Alboin probably reached out to Baian through Sigebert. Alboin was either the husband (or the very recent widower) of Sigebert’s sister, Chlodsuinda, and since Sigebert was already in contact with Baian, he served as an ideal facilitator.

Baian drove a hard bargain. He demanded that the Lombards surrender 10% of their own livestock immediately (presumably to help support the under-provisioned Avars through the severe winter of 566/7). In the event of victory over the Gepids, the Avars would receive half the plunder and all the Gepid lands.

Alboin, whom I suspect was already contemplating a relocation to Italy, agreed to these terms. He had little interest in Gepid territory, he’d already tried and failed to defeat them one-on-one, and the Eastern emperor had declared his neutrality in the on-going conflict. With no other allies on offer, some horses and cattle seemed a reasonable price to pay.

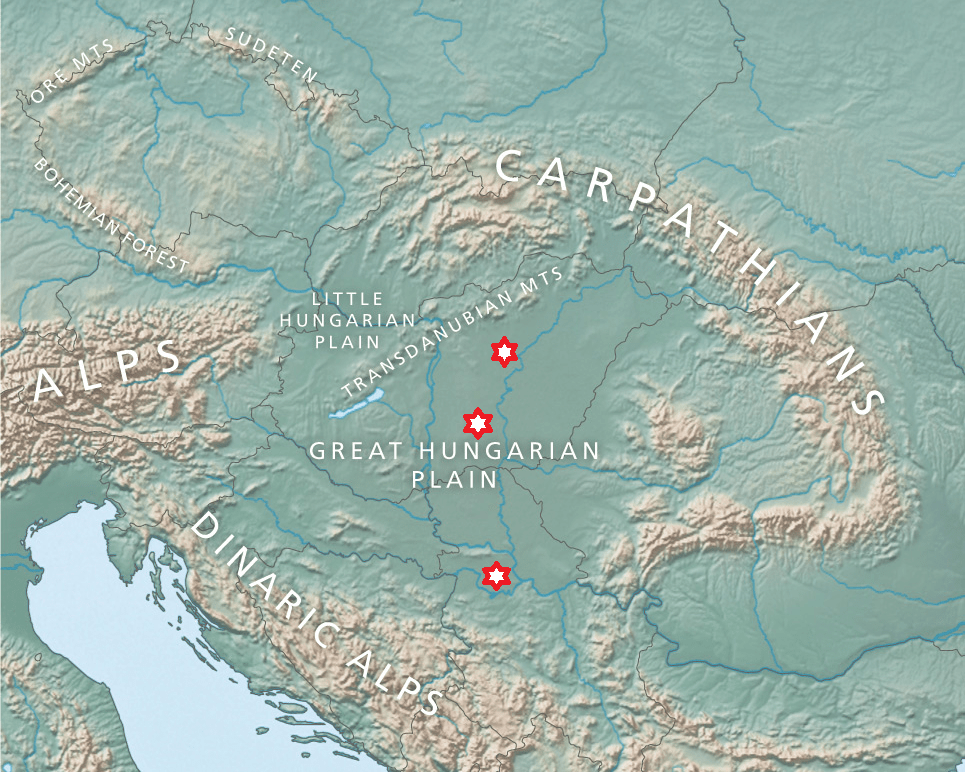

The sources are not unanimous as to how the war between the Lombards/Avars and Gepids unfolded. It is likely to have occurred in the spring or early summer of 567, since this was the traditional fighting season, and by fall of that year, the Avars were besieging Sirmium. Some historians suggest that the Avars remained in the neighborhood of Austrasia throughout the winter of 566/67, then followed the Morava onto the Little Hungarian Plain, passed close by the lands controlled by their Lombard allies, and fell upon the Gepids from the north. This makes sense given the last known location of Baian’s Avars in 566. However we also have reports that he promised to “withdraw” from Frankish lands following negotiations with Sigebert. It’s unclear how far the Avars actually went.

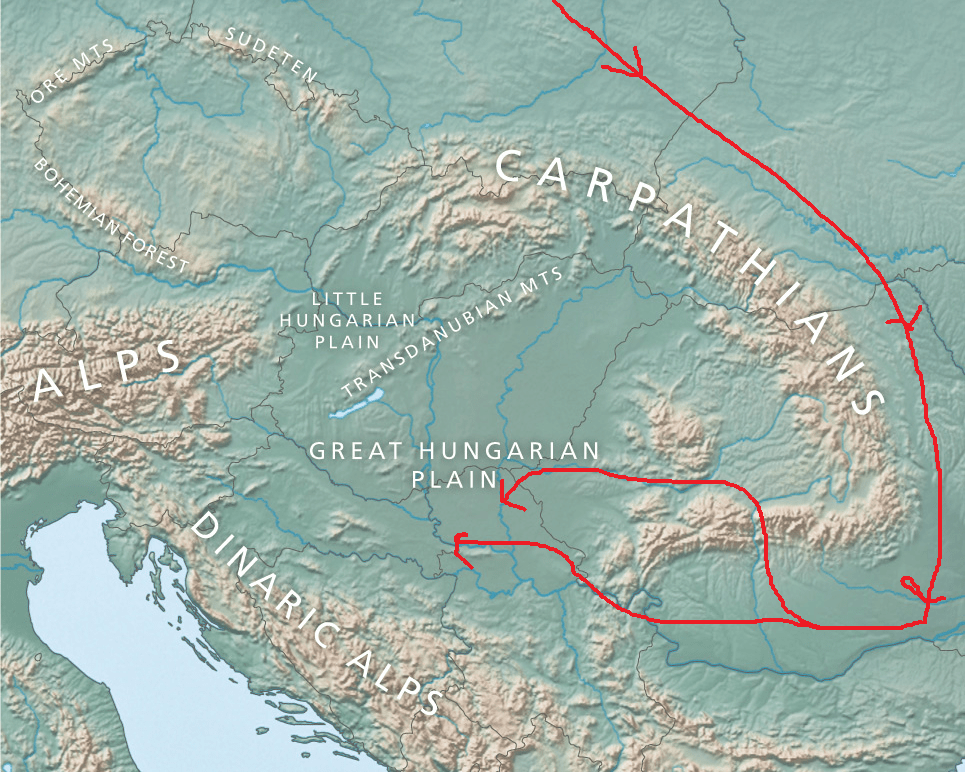

Some historians suggest that the Avars returned to their familiar staging ground on the lower Danube. They then broke through the Gepid defenses in the east. They may have continued toward Sirmium, or followed the Olt north and the Maros west to reach the middle Tisza.

I’ve even seen it suggested that the Roman emperor, who was ill-disposed toward the Gepids, allowed the Avars to cross the lower Danube and approach Gepidia from the south. I must admit, this seems highly unlikely.

There is also little agreement on the details of the final battle itself. The 8th century Lombard chronicler, Paul the Deacon, describes how Cunimund led his army against the Lombards, but on the eve of battle, he learned that the Avars had launched an attack on another front. He chose to face the Lombards first, but he was slain by Alboin. According to Paul, the Avars did not play a major part in the conflict. In this scenario, the final showdown between the Gepids and the Lombards probably unfolded in the marchland between the Danube and the middle Tisza (roughly midway between the core settlement areas of the two peoples). It becomes somewhat more believable that the Avars opened a second front by entering Gepidia in the south and/or east, although they could also have come from the north.

Bishop John of Epheseus, writing closer to the events in the 6th century, paints a very different picture. According to him, it was Baian–not Alboin–who dealt the crushing blow to the Gepids. Many historians suspect that Lombard historiography distorted the actual events to burnish the heroic reputation of Alboin and his people. According to this interpretation, Baian decapitated Cunimund and had a cup made from his skull–in keeping with the customs and beliefs of the steppe peoples. Only later did he make a gift of this trophy to his ally, Alboin. In this scenario, the final battle between the Gepids and the Avars could have occurred anywhere in Gepidia–between the Danube and Tisza, along the Maros, even quite close to Sirmium. Either a northern or an eastern approach by the Avars is possible.

But is it really believable that Baian would lead his army all the way back to the Lower Danube after his second clash with the Franks?

I think there’s an argument to be made, and it hinges on Sirmium. Both Alboin and Baian would have wanted to reach the city first. Despite the agreement that the Avars would get the entire territory of Gepidia, I bet Alboin would have tried to hang on to Sirmium if he managed to take it. Likewise, Baian appreciated the strategic importance of the city, and if his people entered Gepidia further south, they would be almost guaranteed to reach Sirmium before the Lombards.

Of course, I suppose there is a third option, one I’ve yet to come across in my research. The Avars could have split their forces and entered Gepidia from multiple directions. The south-eastern division would have headed for Sirmium (possibly defeating Cunimund along the way,) or the northern division could have dispatched the troublesome Gepid king elsewhere. The Avars already ruled over several subject peoples and used them as auxiliaries. Some of these, including Slavs, had engaged in hostilities with the Gepids along the lower Danube in the mid-560s. Perhaps one of these, under the command of a trusted lieutenant or son, led a drive into Gepidia from the south-east.

So, where do I come down? I think that Baian probably overwintered near the borders of Austrasia and entered Gepidia from the north. I suspect it was the Avars who defeated the Gepids in battle, and Baian had Cunimund’s skull turned into a ceremonial vessel which he later presented to Alboin.

But that’s not exactly what happens in my story. It’s much more dramatic if Alboin defeats Cunimund–and kills him personally. It explains the depth of Rosamund’s rage and resentment and raises the stakes for her. In this sense, it doesn’t matter what I think actually happened. The story has its own prerogatives, and so long as it doesn’t grossly distort the possible facts, I’m happy to go along. The final battle will occur when and where the story needs it to occur. The Avars will approach from the direction I choose–the one that serves the story best. One thing is certain: Alboin will kill Cunimund. And Rosemund will be left with a big axe to grind.