| Widsið maðolade, wordhord onleac, se þe monna mæst mægþa ofer eorþan, folca geondferde; oft he on flette geþah mynelicne maþþum. Him from Myrgingum æþele onwocon. He mid Ealhhilde, fælre freoþuwebban, forman siþe Hreðcyninges ham gesohte eastan of Ongle, Eormanrices, wraþes wærlogan. Ongon þa worn sprecan | Widsith spoke, unlocked his word-hoard, he who had traveled most of all men through tribes and nations across the earth. Often he had gained great treasure in hall. He belonged by birth to the Myrging tribe. Along with Ealhild, the kind peace-weaver, for the first time, east of the Angle, he sought the home of Eormanric, king of the Ostrogoths, hostile to traitors. He began then to speak at length: |

| …. Swylce ic wæs on Eatule mid ælfwine, se hæfde moncynnes, mine gefræge, leohteste hond lofes to wyrcenne, heortan unhneaweste hringa gedales, beorhtra beaga, bearn Eadwines. | I was in Italy with Aelfwine too: of all men he had, as I have heard, the readiest hand to do brave deeds, the most generous heart in giving out rings and shining torcs, Eadwine’s son. |

| …. Ond me þa Ealhhild oþerne forgeaf, dryhtcwen duguþe, dohtor Eadwines. Hyre lof lengde geond londa fela, þonne ic be songe secgan sceolde hwær ic under swegle selast wisse goldhrodene cwen giefe bryttian. | And then Ealhhild, Eadwine’s daughter, noble queen of the household, gave me another; her fame extended through many lands when I used my song to spread the word of where under the heavens I knew a queen, adorned with gold, most generous of all. |

The preferred histriographic term for Rosamund’s era is “late antique” or “early medieval.” The old descriptor–“the Dark Ages”–with its ominous insinuation of ignorance, brutality, and decline, has fallen out of favor. And yet, this term persists in the popular imagination.

But if the 6th century of Rosamund and Alboin is dark, that is mostly down to our ignorance, not theirs. Very few primary sources from the early middle ages survive. There are many things we simply do not–and cannot–know . But this profound obscurity makes the sources we do have all the more precious and intriguing.

One such resource is the poem Widsith, which was included in the Exeter Book, a collection of Old English poetry. Although it was transcribed in the late 10th century, the poem itself is probably much older. It may reflect an oral tradition dating back as far as the 5th or 6th century. The composition was altered and amended over several hundred years, until it achieved the form we know today.

In modern English, Widsith means “far-traveler,” an apt description of the poem’s narrator, a wandering minstrel who purportedly traveled throughout Europe and the Middle East, encountering famous figures from the Germanic heroic age along the way. Despite its first-person voice, the account is definitely fictional. “Widsith” claims to have met heroes from the 4th through 6th centuries–if true, he must have been one elderly minstrel! Additionally, the poetry…isn’t great. Large sections of Widsith are simply lists–of kings, of peoples, of noble warriors. But in a sense, the poem’s least artistic sections are the most enticing for modern historians. Some of the people and tribes mentioned would be otherwise completely unknown.

In Widsith, we can catch a glimpse of one figure of particular interest–Ealhhild, daughter of Eadwine and sister of Aelfwine. If these names are unfamiliar, it is because they’ve been passed through an “Anglo-Saxon filter.” Eadwine is Audoin and Aelfwine is Alboin. The traveling minstrel supposedly encountered Alboin in Italy, and he is described as a bold and generous king. According to the Lombard chronicler Paul the Deacon, Alboin was well-known heroic figure among the continental tribes. It seems safe to say that his fame traveled to Britain with the Angles and Saxons.

Sprinkled amidst the catalogues of heroes and kings, there are traces of an actual narrative. Ealhhild, it is claimed, is Alboin’s sister. Widsith the bard travels with her to the lands of Eormanric, king of the Goths. He is richly rewarded by Eormanric and even receives a precious gift from Ealhhild herself. In gratitude, he composes a song in her honor that spreads her fame far and wide.

While the sequence of events makes a broad sort of sense, the details are somewhat contradictory and ambiguous. We know who Ealhhild is, but where is she coming from? And why does she go to Eormanric?

The most obvious interpretation is that the minstrel was part of Ealhhild’s bridal retinue when she journeyed to Gothic lands to marry Eormanric. The entire episode is a historical impossibility. A sister of Alboin would have lived in the 6th century. Eormanric (aka Ermanric) was a 4th century Gothic king. It’s important to keep in mind that Widsith–itself very old–is describing people and places a half-millennium older. The gauzy haze of legend hangs over the poem, a world in which a minstrel can travel from Scotland to India, from Lapland to Egypt and meet the most famous personages of three centuries in a single lifetime. It feels as though anything and anyone can be included in the travelogue, so long as they existed in the all-encompassing “past.” The pairing of Ealhhild and Ermanric is best regarded as a literary conceit–a famous king paired with a princess of illustrious descent. Better for her if they were not married–Ermanric was notorious for unjustly killing his wife (elsewhere named Swanhild) on suspicion of adultery.

Some older critics read the poem differently and suggested the Ealhhild was the queen of Widsith’s lord, Eadgils, king of the Myrgings (a Saxon tribe). But why then would she travel to Eormanric’s court? It was not usual for queens to join diplomatic missions or serve as hostages.

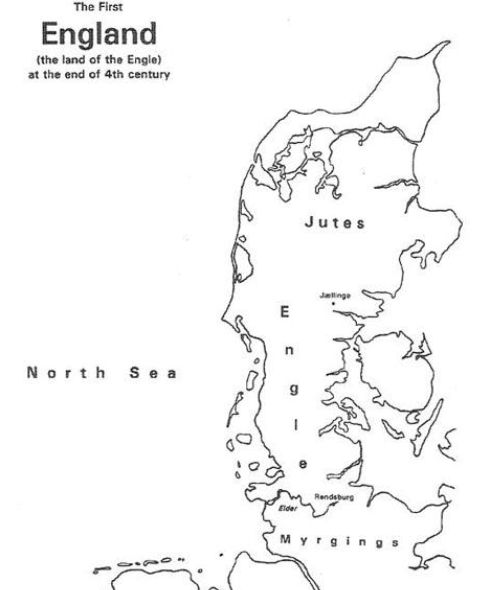

Nonetheless, this connection of Ealhhild with the Myrgings intrigues me. The Lombards once lived in the vicinity of the Myrgings close to the mouth of the Elbe, and they maintained relations with their former Saxon neighbors. When Alboin and his Lombards moved into Italy, they were reportedly accompanied by 20,000 Saxon warriors along with their households. Alboin obtained their assistance in exchange for settlement rights on the Italian peninsula. I am very tempted to have Alboin’s sister play a part in the negotiations. Perhaps the deal might be sealed with her marriage to a Saxon chieftain?

The one thing I feel pretty comfortable saying is that Alboin’s sister existed. Widsith is quite unambiguous on that score, identifying her, her brother, and her father by name. The fact that the details of her life were confused or fictionalized is a secondary consideration. It also gives me the leeway to depict her as I like. All that remains is to de-anglicize her name. My best guess is Alahhild.