As I prepared to write Rosamund’s story, one of my first tasks was to place her in a political and geographical context.

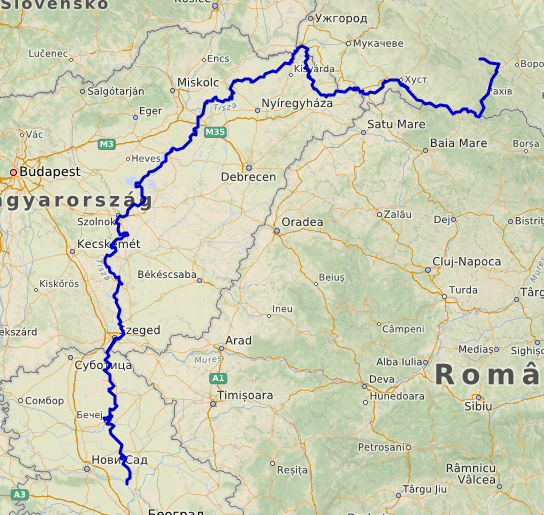

When the Gepids first appear in the historical record, they reside along the upper reaches of the Tisza River. This would have been a less than ideal environment, pressed up against the mountains and exposed to peoples funneling off the steppes into the Great Hungarian Plain. The bulk of their population probably remained in this area throughout the period of domination under the Huns. They would have served as a sort of buffer nation. Along with the Goths, they were supposedly the Germanic tribe most favored by Attila. The proximity of their settlement area to nucleus of Attila’s empire on the Hungarian plain probably reflects this preferred status.

With their victory over Attila’s heirs at the Battle of Nedao in 454, the Gepids moved south along the Tisza onto the open Hungarian Plain.

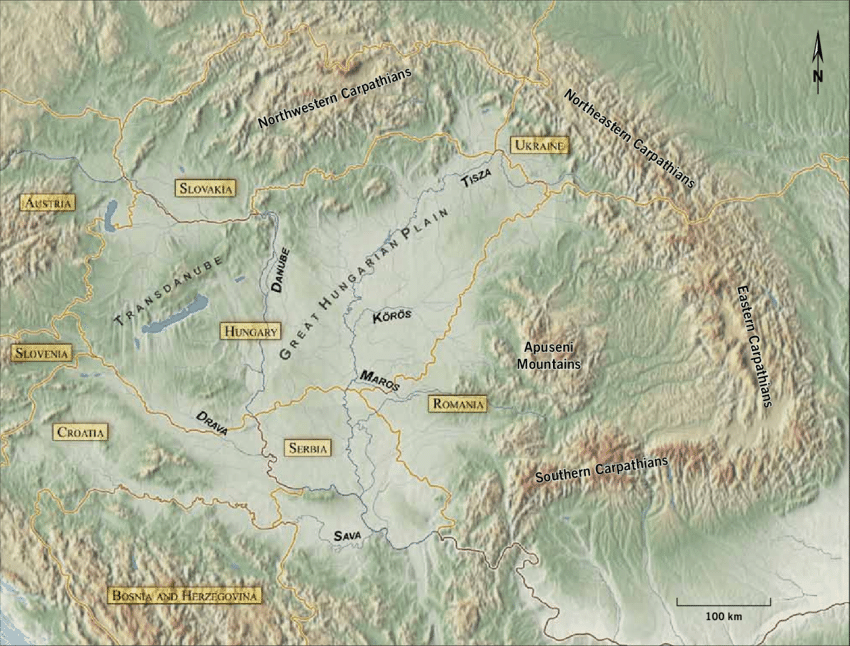

It’s important to keep in mind that this entire area would have looked quite different in the 6th century. The rivers had not been tamed in any significant way. Tributaries would have crisscrossed the plain and flooded regularly. Wetlands appeared alongside many waterways and at confluences. Lakes and ponds may have been attractive features for the hunting and fishing they offered. Many of these natural features have been obscured by modern water engineering and land improvement projects.

The plain may also have been somewhat more wooded, dotted with small, scattered groves. Poplars and willows dominated low, wetlands. Better-drained areas may have supported trees like oak and maple. Most of these woodlands have since vanished due to agricultural deforestation and timber harvesting. Today, you can possibly catch a glimpse of what Rosamund’s world might have looked like in a few national parks and nature reserves.

Summers would be quite hot and also wet. Winters would often be bitterly cold. The middle Danube would have regularly frozen during the winter.

The Gepids dominated the eastern half of the Carpathian Basin for nearly 100 years. The “Gepid heartland” lay to the east of the Tisza, roughly between the Maros and Körös Rivers. Excavations of cemeteries in this area suggest Gepids lived here for several generations. They also followed the Maros eastward onto the Transylvanian Plateau. Although that area was more sparsely settled, its mines provided important resources. At the peak of their power in the 6th century, they may have also occupied (or at least garrisoned) the area between the Southern Carpathians and the Danube. In general, the Tisza River formed the western border of their territory and the Danube the southern, with one exception–the area around Sirmium.

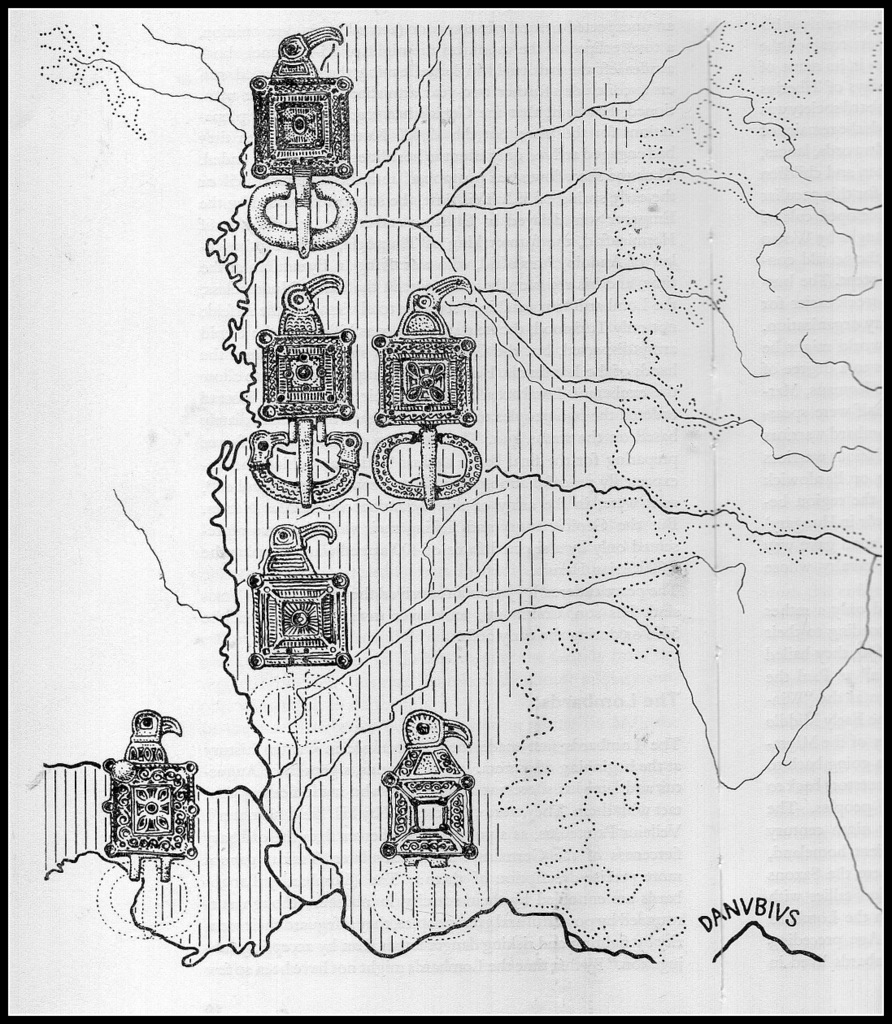

Using archeological discoveries as an imaginative jumping-off point, I began to develop a few key locations within the kingdom.

First, there was the district around Sirmium. This extended roughly from the old Roman town of Cibalae in the west to the Danube in the east. I imagine that this area was somewhat distinct from the rest of Gepidia. Its prize jewel was the Roman city of Sirmium, much reduced from its heyday, but still an economically and strategically important stronghold. Here, one could find a remnant Romanized population (although what “Roman” means in this time and place is an interesting topic for another day.) The Gepids (and/or their Herul vassals, who were also settled in this region) would have occupied the surviving Roman forts along the Danube and probably controlled most traffic along this stretch of the river. From this region, the Gepids could also control (and profit from!) the flow of other barbarian raiders into the Roman empire. For this reason, it was the most prestigious and strategically valuable of all their territories.

Scattered settlements along the Tisza linked the Sirmium region with the Gepidic heartland to the north. The first major ford across the Tisza occurred near Szeged. In Roman times, a trading post called Partiscum existed somewhere nearby. This is also a supposed site of Attila’s capital, described as an impressive “wooden city” on the plain, complete with Roman baths made from imported stone. In my telling, the royal residence in this neighborhood is called Hunabaúrgs (“Hun-town”) in memory of Attila’s long-lost residence. Hunabaúrgs is important due to its position near the intersection of the Tisza and Maros rivers–the watery crossroads of Gepidia.

Moving north, there is another large settlement near Hódmezővásárhely. The modern town takes its name from a lake that existed in the area in earlier times–Lake Hod, or “Beaver Lake.” (Incidentally, this is one of the wildest Hungarian place name I’ve come across, and all my attempts to determine the location of the lake, its characteristics, and the history of its aquatic rodents has been in vain. If only I could read Hungarian!) The Gepid settlement was on the northeastern shores of the lake. I, likewise, gave it the name Bibralagus (“beaver lake”).

I chose to place the largest royal residence in the district near modern-day Szentes. There have been many Gepid villages excavated in this area. It was also located close to a crossing over the Tisza. This seems to have been a relatively wet area defined by numerous lakes and small tributaries. No doubt the Gepids exploited these ecosystems. The loose inspiration for the royal residence is the excavated site at Szentes-Nagyhegy. Here, archeologists found evidence for the presence of many warriors, aristocratic women, and slaves, as well as artifacts suggestive of trade with both Northern tribes and East Romans. This, to me, suggests diplomatic gift-giving and commerce among the elite strata of society. Apparently Nagyhegy means “high mountain” in Hungarian (although I’ve struggled to find so much as a hill in the area.) Be that as it may, I’ve given the Gepid town the name Godahlains, or “good hill,” which seems about the best you could hope for in such a flat area.

The northern edge of the Gepidic heartland seems to have been around the modern town of Szolnok. There was another ford across the Tisza in this area. Archeologists have found evidence of aristocrats and heavily armed warriors in the vicinity, possible associated with defense of the bridgehead.

Why the need for so many royal estates and residences? I suspect that the Gepid royal court–like those of other Germanic kingdoms of the period–traveled with some frequency. Although later medieval royalty often visited the estates of their various vassals in, rulers in this period tended to stick to their own landholdings, which were substantial. I imagine they would have traveled on a seasonal basis for a variety of reasons.

In the summer, for example, the queen and the domestic household might occupy a safe position in central “Gepidia,” since the king and his army would often be away at war. In the fall, the court might relocate to the king’s preferred hunting grounds, perhaps closer to the hills and forests. They might settle in the Tisza-Maros region in the season for councils, when proximity to the communicative waterways of the territory would be most useful. The royal court might observe religious holidays like Lent and Easter at estates chosen for their high-status churches or precious relics. Campaign season would start between Easter and Pentecost, and the entire cycle would begin again.

Obviously, all of this is extremely speculative. I can only try to strike the right balance between fact, inference, and conjecture.

Pingback: The Gepid State, Part 2–Searching for the Invisible | A Queen's Cup