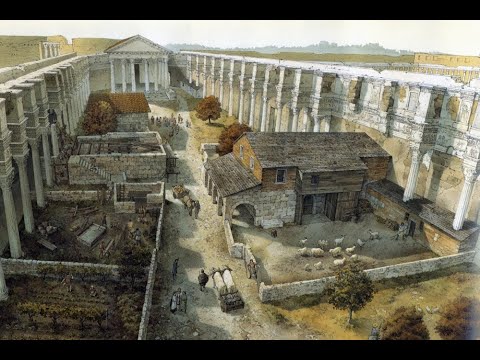

Rosamund would have presumably spent some amount of time in Sirmium (now Sremska Mitrovika, Serbia), which was under Gepid control in the mid-6th century. This city on the banks of the Sava was once the capital of the Roman province of Pannonia Inferior and, in the 3rd-century, served as a capital of the empire. It boasted forums, basilicas, enormous baths, an aqueduct, a hippodrome, an imperial palace complex, a fortified circuit wall, an extramural necropolis, and numerous urban villas, to say nothing of its more workaday businesses, marketplaces, and habitations. In its heyday, it would have looked something like this…

There aren’t many novels set in this part of the world in the 5th and 6th centuries (at least in English), but those that I’ve been able to find seem to treat Sirmium as a bastion of Roman society, its glory tarnished by the travails of history but still largely intact. My research suggests this was far from the case.

From Tommaso Empler Cultural Heritage: Displaying the Forum of Nerva with New Technologies

First of all, it’s important to keep in mind that, although Sirmium was an important imperial city and former capital of the empire, it was not an enormous settlement on the scale of a Rome or Constantinople. At it’s zenith, it’s population probably topped out around 15,000. The city was erected over a series of marshes and swamps–undoubtedly a feat of Roman engineering. But the soft, unstable soil made the construction of monumental edifices a challenge. Rather than classic Roman insulae (essentially multi-story apartment blocks,) most regular residents of Sirmium lived in more modest, single-story dwellings. The wealthiest residents apparently preferred to live outside the city on luxurious country estates. Sirmium would have been a pungent place, blending pre-modern urban odors with the scents of the surrounding wetlands. It may have been a relatively unhealthful environment as well, with swarms of insects transmitting diseases to the city’s inhabitants. Of course, the Romans did their best to keep the marshes in check, and centuries of infill would have reduced their natural extent.

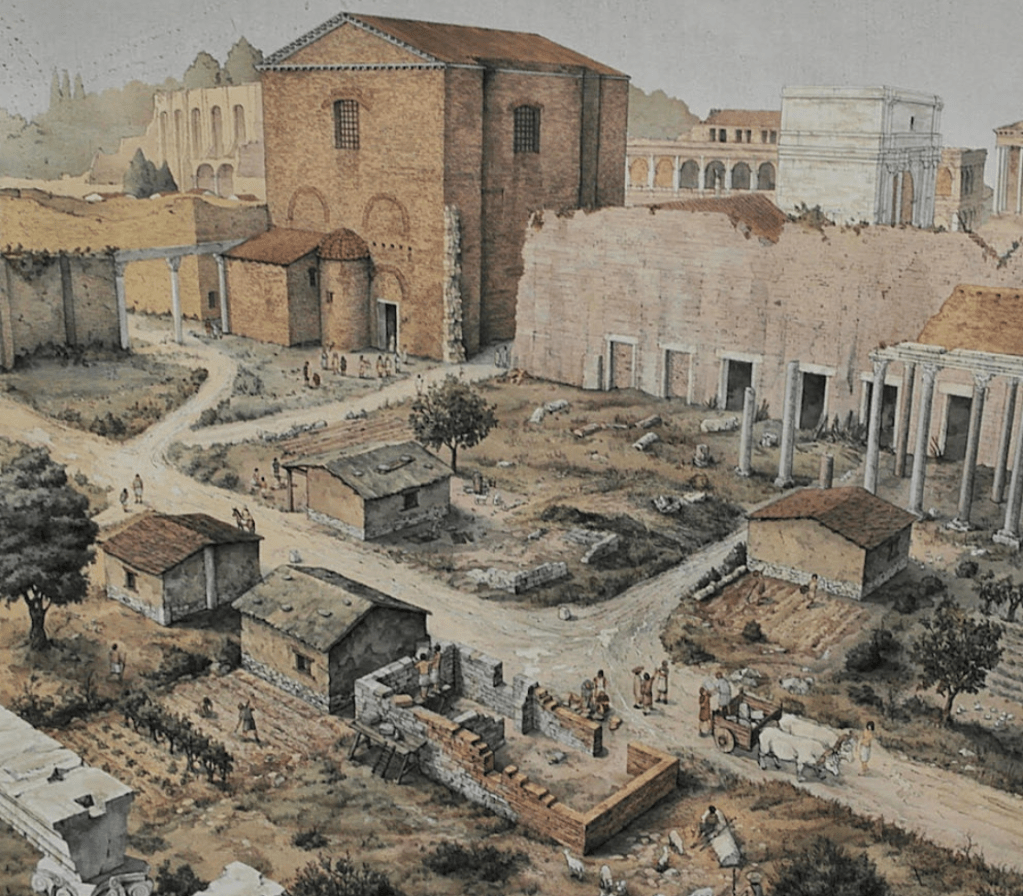

As early as the late 300s, Sirmium underwent a process of “ruralization” and “barbarization.” Waves of invaders damaged or destroyed many parts of the city. The justifiably nervous population began to inter (and re-inter) their dead within the city walls. The city’s population declined. The residents that remained clustered in the southernmost part of the city, close to the river Sava, which had become the main source of water for the settlement after the aqueduct ceased to function. A new earthen rampart bisected the city to fortify the inhabited districts. The swamps and wetlands probably reemerged in the absence of ongoing abatement projects.

The only monumental edifice constructed after the year 400 was the urban basilica of Saint Demetrios. The residents of Sirmium buried their dead both inside and around the building. Even so, after extensive destruction by the Huns, people began to build their houses and workshops over the graveyard. It is likely that the Huns razed the basilica itself around 441, although for the purposes of my story, I’ve left it standing (at least for the time being.)

By the 5th-6th century, most of the imperial and public spaces of Sirmium had been ceded to the local population for their use. The open arena of the hippodrome, the ruined granaries, the tumbled peristyles of formerly luxurious urban villas, even the forum and the imperial palace complex were filled with primitive huts, workshops, and lean-tos. Open hearths were cut into mosaic floors. The cryptoportucus of the hippodrome became a dumping ground for rubbish and cleared rubble.

Collapsed roofs and damaged walls cluttered the urban environment. Some structures were probably taken down purposefully. Inhabitants constructed new buildings in open or cleared spaces on a surface of carefully leveled destruction. They built in ephemeral materials–wood, thatch, wattle and daub. Some houses and enclosures were built using recycled materials (spolia) lifted from the surrounding rubble and mortared with mud. Possibly these enclosures were used as gardens or animal pens. Most construction was haphazard and bore no relation to the original layout of old Sirmium. The days of Roman city planning were long gone. Barbarian newcomers settled the city and adapted the existing spaces to their own habits and need. Those “Romans” who remained would have been virtually indistinguishable from their barbarian neighbors.

Traces of old Sirmium still survived in Rosamund’s day and might have struck her as particularly impressive in light of what the city had become. The walls of the hippodrome and of the imperial palace complex were still standing, even if not to their original height. These areas would have provided shelter and protection during times of danger. Some part of the thermal bath complex survived (though probably no longer in normal operation due to the destruction of the city’s aqueduct/plumbing systems.) Still, residents climbed onto the thermae roof to see the approach of an Avar delegation post-567.

Christ, our Lord, help our city halt the Avars. Protect the Roman Empire, and he who has written this. Amen.

Inscription scratched into a rooftile in Sirmium, approximately 582

The city’s original East-West commercial road connected residential areas to the basilica of Saint Demetrios; it would have still functioned as the main artery of the town. Along the eastern part of the road, some of the substructure of the hippodrome seating had been turned into a stand-alone building. Although the vaulted ceiling had collapsed (and was probably replaced with timber and thatch), the tall stone construction would have been quite impressive. Nearby stood two comparatively large and luxurious stone residences built in the late5th/early 6th century. They were modest by earlier standards, but next to the wattle-and-daub huts clustered nearby, they would have seemed like palaces. They may even have enjoyed Roman-style underfloor heating. I’ve treated them as royal residences during the period of Gepidic occupation. Presumably Rosamund would have known them well.

N.B. Much of the published work on late antique Sirmium is not in English. Any mischaracterization of the interpretation of specific excavations can almost certainly be chalked up to the sad state of my college French. If you know more about this time/place–tell me about it!

Pingback: A Geography of “Gepidia” | A Queen's Cup

Pingback: The Gepid State, Part 2–Searching for the Invisible | A Queen's Cup