As is probably apparent by the working title of my manuscript, cups play a central role in Rosamund’s story. Obviously the first cup that comes to mind–and the most infamous–is the one made from her father’s skull which ignites her eventual vengeance. But cups, the liquor they held, and the words spoken over them may have had a special significance in Rosamund’s culture.

My major inspiration in this regard is Michael J. Enright’s Lady with the Mead Cup, a fascinating analysis of women’s roles in barbarian drinking culture. He proposes that women–in particular queens–served as cup-bearers in rituals that helped to create, reinforce, and clarify the bonds between a warband/retinue and their lord.

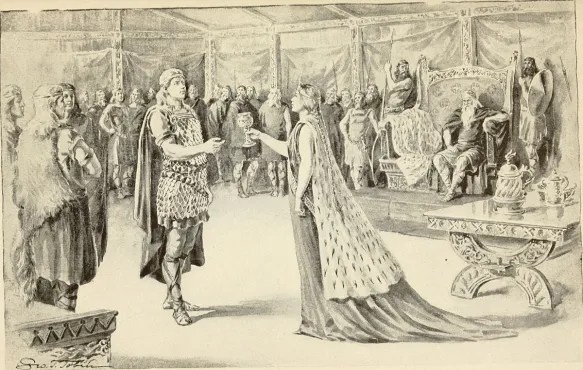

In the first part of my novel, I contrived to give Rosamund the role of cup-bearer in her grandfather’s court. This allowed me to bring her into the masculine space of the king’s hall. The hall wasn’t merely a place for drinking, feasting, and merrymaking. It was a site of ritual binding where the king’s diverse followers were transformed into a symbolic family–a space of prophecy, oath-making, memory, and tradition. Liquor served as a sort of ersatz blood for ritual purposes; sharing from the same cup created a symbolic familial bond, with the king as father and his lady as mother.

There was an understanding that prophecies were often spoken over wine. Oaths made over the cup, particularly those about women or provoked by women, were considered especially potent. Liquor and women were closely related in the barbarian imagination. They served the ritual drink, received and incited oaths, and bound the community to the king. Sometimes women were even referred to as liquor (a fascinating concept for another day.).

In my story, the first “queen’s cup” is the vessel Rosamund bears to her grandfather and his followers in the hall. So what would this ceremonial cup look like? Here are several options, each of which has implications for the various cultural influences in the Gepid court.

Option #1 is something like this fabulous early 6th century chalice from the Treasure of Goudron, found in France. It was found in a hoard together with a matching paten, so it was possibly a sacramental chalice. The style is Roman, but the decoration is “Germanic.” I especially love the bird-head handles, and the cloisonné hearts and flowers are very striking. The fusion of “barbarian” and Roman styles is appealing. Something that doesn’t come across in the pictures is the scale. This chalice is tiny, only a few inches tall! It’s hard to imagine something this size being raised in a raucous hall. A larger version would be incredibly precious.

Option #2 is a roughly contemporaneous bowl of East Roman manufacture, probably a luxury item made for export. This is a more bowl-like form, but with a similar footed base. This bowl is silver, not gold, and it’s also quite small–only about 6 inches in diameter. Still, I do tend to imagine a cup with more heft since it is used in public ceremonies. Plus, that rim does not look great for drinking.

Option #3 takes us away from the Roman world and toward another cultural pole. This striking cup dates to the early 5th century and probably belonged to a rich Hun, although there’s some debate as to whether it’s of Alanic or Persian origin. It’s an electrum alloy of gold and silver, and the gaps were probably once filled by glittering red glass roundels. It would have been watertight for drinking. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to get any sense of its scale. Whatever its origin, it is not a Roman-style cup. The Gepids were former subjects of the Huns and seem to have prospered during that time. In my novel, several high-ranking members of Thurisind’s court are descended from individuals that would have identified themselves as Hun, Alan, Sarmatian, Vandalic, etc. I do think they would have retained some choice treasure, ritual practices, and political iconography from that period of their history, and that’s the feeling I get when I imagine something like this as Rosamund’s cup.

Option #4 is actually my favorite. This particular specimen is from the Treasure of Szilágysomlyo found in what is now Șimleu Silvaniei, Romania. It dates to the 5th century and has sometimes been associated with the Gepids. You will notice the little buckle on the side. That is because this cup was meant to be worn on the belt or possibly hung from a saddle. I haven’t been able to find an exact measurement on this (or similar) bowls, but poking around the virtual “Early Migration Era” room at the Hungarian National Museum, it looks like an adult man could hold it easily with one open hand, while a young girl would probably need two–in other words, exactly the size I had in mind. Cups like this were probably used in libation rituals and in ceremonies to seal oaths and agreements. The fact that it has a rounded bottom is key to its symbolism–it cannot be put down until the drink has been fully consumed, the oath wholly undertaken. To my mind, this wide, jeweled, round-bottomed vessel is closest to what Rosamund carries in her grandfather’s hall.

Pingback: The cup(s) in question–Part 2 | A Queen's Cup